First Technion Society (from 1924)

Four years passed before the Technion was refurbished and ready for teaching. Only very limited funds were available for the most necessary renovation work to remedy the poor condition of the building at the beginning of the 1920s. In addition to the years of neglect during the First World War, not only the furnishings but also the laboratory utensils had been looted: During the British Mandate period, the ladies of the society are said to have used the glass chemical flasks to pickle their pimples.

In 1923, Albert Einstein visited the empty Technion building on his way back from a lecture tour in Japan. His ship anchored in Haifa, he had the architect Alexander Baerwald show him the building and, as a physicist, supported the plan to open an institute for technology and science in Haifa in the near future. After his return to Germany, he called together wealthy Jewish personalities in Berlin to establish the world’s first “Technion Society”. Baerwald and Einstein knew each other from Berlin, where they had played chamber music together in a quartet; Einstein played the violin, Baerwald the cello. Einstein’s commitment consisted primarily in the establishment of a new “Society for a Technical Institute in Haifa”, which was founded in his apartment in Berlin-Schöneberg, Haberlandstraße 5, on April 17, 1924. This society solicited donations for the Technion and customs relief or exemption from customs duties for the shipment of furnishings. The global currency crisis led to a significant drop in donations. The donations therefore consisted mainly of practical items, such as technical instruments and furniture, in order to make the former building fully usable again.

The World Zionist Organization also provided a small budget, and in December 1924, the first students enrolled in architecture and civil engineering at the Technion. Female engineering students were among them right from the start.

The period from 1924 saw the opening of the Technion, the first successful years of teaching, but also repeated financial bottlenecks.

The university in Haifa had suffered great financial hardship in the early years, and the employees’ contracts were terminated on September 30, 1931. From then on, they continued to work without pay for of the students and the survival of the institute. The influx of many excellently trained engineers and technicians from Germany finally brought about a financial turnaround for the university, large donations were again made from other countries and the high tuition fees that had been introduced in the meantime could be waived again.

Intermediate times (until 1981)

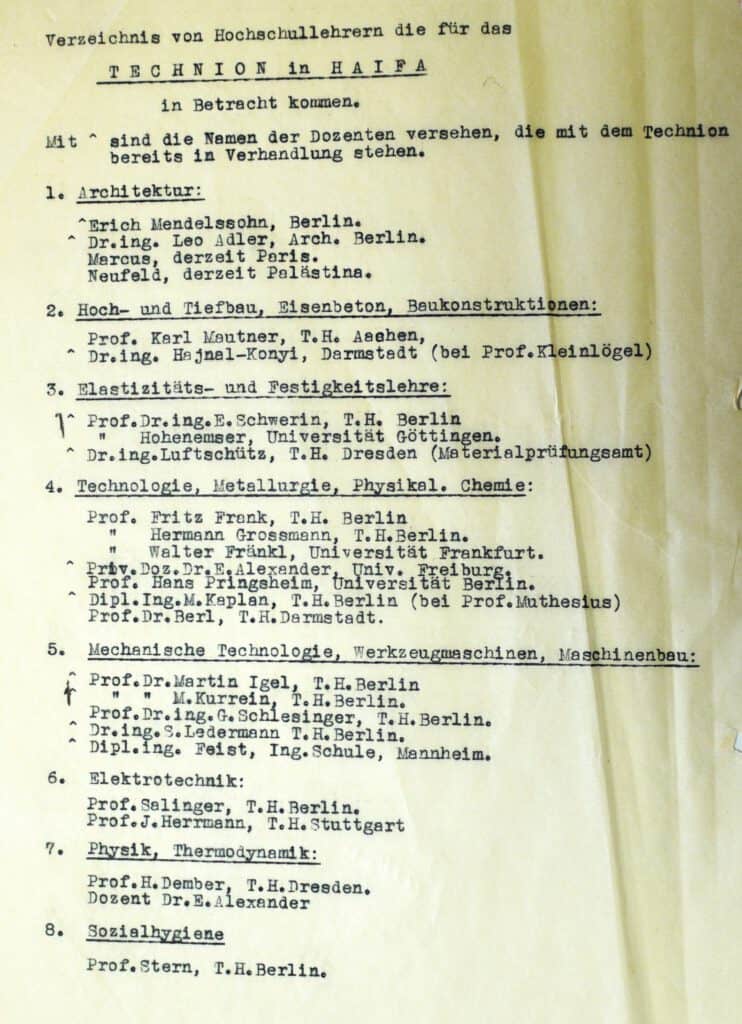

From 1933 onwards, Jewish professors from Central Europe increasingly sought refuge and employment at the Technion. The few departments at the time could only accommodate a small proportion of the scientists. Thanks to its distinguished European professors, the Technion was already a recognized scientific university at this time, even though it was not officially given this name until the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

Prof. Sidney Goldstein, originally from England, founded the Faculty of Aeronautical Engineering back in 1949 and expanded it against all odds. Together with the engineers trained at the Technion, she helped the aircraft industry in Israel to flourish. Prof. Goldstein bundled academic regulations at the university into formal guiding principles of Western standards, which formed the basis for the academic development of the university.

At the beginning of the 1950s, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion selects a 1.2 km2 area for the new Technion campus so that the university can adapt to the needs of the steadily increasing number of students. Foundation stones for the new buildings are laid on the saddle of Mount Carmel in 1953 and the number of faculty members rises to 206. During the more than 10-year term of office of President Lt. (Gen.) Yaakov Dori, a science faculty, a graduate school, the “Research and Development” department, which has been transformed into a foundation, and numerous new engineering programs are established. Previously taught as courses, subjects such as mathematics, chemistry, physics, mechanics and agricultural engineering soon grew into their departments, and the American Technion Society, founded in 1954, wrung a promise from Prime Minister Ben-Gurion to receive an additional dollar from the Israeli state for every dollar donated to build the new campus. The other Technion companies worldwide were soon involved in this endeavor.

In the 1960s, the Technion opened its doors to hundreds of African and Asian students from developing countries and offered programs in English that led to a better economy with the help of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and UN agencies in the respective countries. Meanwhile, the number of students, which had started with 17 enrollments in 1924, grew to 1,973 in 1959 and 5,756 in 1973.

The Faculty of Medicine, which was opened in 1969, was associated with great expectations of fruitful cooperation between the engineering and medical faculties. These came to fruition decades later in the blossoming of medical technology and in the 2020s in the combination of artificial intelligence with the life and natural sciences.

A resumption of cooperation with Germany was out of the question for a long time: from 1956 onwards, the Technion’s Board of Governors was chaired by former judge Mosche Landau, an avowed opponent of Germany and the main prosecutor in the Eichmann trial. Under his presidency, the Technion, once a “German university”, was unable to establish official relations with Germany and German universities. There was no question of the Israeli side re-establishing a friends’ association. As the university president’s hands were tied, the then Vice President for Research at the Technion, Prof. Dr. Joseph Hagin, began to establish initial contacts with Germany in the 1970s. He paved the way for academic cooperation at the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in Bonn together with Ministerial Director von Hase and the Head of the Department of Physics at the University of Göttingen, Prof. Dr. Peter Haasen.